Saturday nights training pigs in an MRI scanner

MRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is a noninvasive imaging technology commonly used in research to observe the brain’s reaction to stimuli. The MRI scanner is very noisy and requires the subject to remain perfectly still, as every slight movement will distort the image. Because of this, traditional research on animals using fMRI scans requires sedating the animal. But, this practice raises ethical concerns and distorts the brain’s response to stimuli. If we want to see the brain activity of another specie, we need to find a way to motivate them to remain completely still, for several minutes, in a noisy and confined space. Some dogs would do anything for a treat, so naturally they were the first nonhuman animal to voluntarily participate in a non-restrained fMRI scan. But can we get other animal species to perform this very complicated and demanding behavior?

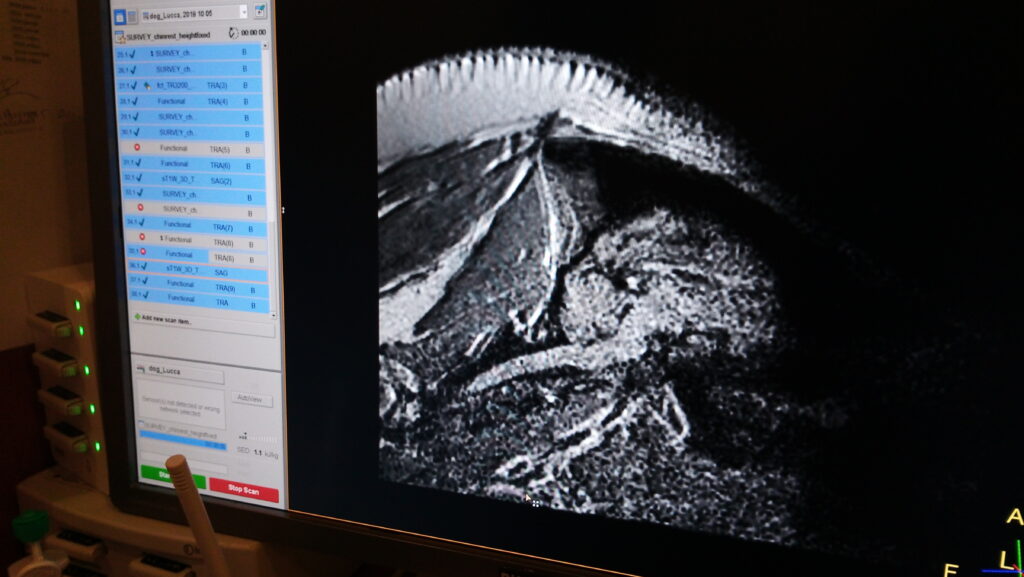

In 2018, I joined the Neuroethology of Communication Lab, supervised by Dr. Attila Andics, as an animal trainer. One of my primary tasks involved developing a training program for minotaur pigs to participate voluntarily in non-restrained fMRI scans. The pigs involved in the program were companion animals, residing with families in Budapest and living a lifestyle similar to that of most pet dogs.

However, while dogs were selectively bred based on their ability to communicate and cooperate with humans, pigs, being prey animals, were primarily selected for meat production. Consequently, while pigs exhibit high motivation for food, possess social skills, and can solve spatial problems, they are less cooperative, easily frightened, and highly active. To get a pig into an MRI scanner, it must walk into a hospital, climb onto a table, lie down, have ear protectors placed on, be pushed with the table into a crowded and dark tube, and remain motionless for several minutes amidst loud banging noises. Would you be okay with that? Now imagine someone is willing to give you a million dollars to do all of that, are you okay with this now?

Fortunately, pigs love food. They really, really love food. So, for them a piece of cucumber could be considered the equivalent of a million dollars. However, as prey animals, this process goes against most of their natural instincts. Making things even more challenging, gaining access to an MRI scanner is no easy task, and every moment inside the scanner is precious. Therefore, we don’t have much time to waste on training. That’s why it was crucial for this project to break down the different behaviors we wanted the pig to perform into small and simple steps. We trained each behavior separately in a mock scanner located in the laboratory of the Department of Ethology.

When the time came to enter the real MRI scanner, the pig already knew what behaviors we expected from her. Now, we only faced the enormous challenge of getting her into the right “headspace.” The right “headspace” means that instead of panicking due to the loud noises, the cramped space, and the flashing lights, she would relax in the scanner and perform what she had already learned. This turned out to be the most difficult part of the training process.

Luckily, I am a bit of a night owl, and so is the owner of Sari, the pig that we trained. However, Sari herself is not. Nonetheless, this worked to our advantage. Most of our training sessions took place in the MRI scanner on Saturday nights, after Sari had enjoyed a satisfying meal and was ready to doze off in the scanner. Unfortunately, by the time we managed to arrange everything and conduct the first unrestrained, fully conscious fMRI scan with a pig, Hungary experienced an outbreak of African Swine Fever. As a result, we were no longer allowed to transport the pigs to the hospital. Consequently, we were unable to collect enough data to publish an article.

On a personal level, this project taught me a great deal. I first joined the team, I believed that it contradicted most of the pigs’ natural behaviors, and I was one hundred percent certain that it was impossible. Through this project I learned to connect between training behaviors and the individual animal’s (human and pig) natural tendencies.